The Pazzi conspiracy

Anyone who visits the city of Florence hears the story of the Pazzi conspiracy: the Florentine banking family Pazzi, with the support of Pope Sixtus IV, intended to overthrow the ruling Medici. They stood in the way of the Pope’s plans to extend his power over central Italy. So the pope tried to harm the Medici by taking away their lucrative business interests and handing them over to the Pazzi. The Medici fought back efficiently and successfully.

This initial situation was the basis for the idea of robbing the Medici family of its two leaders, Lorenzo and Giuliano. The conspirators chose the cathedral, where a high mass was being celebrated in honor of the newly appointed Cardinal Raffaele Riario, as the location for the assassination. The desecration of the holy place was deliberately accepted in order to gain the advantage of being able to murder both Medici at the same time and thus wrest sole power from the family, which had been left leaderless.

A medal depicts what happened on April 26, 1478

What happened (or rather, what is said to have happened) on April 26, 1478, is depicted on a remarkable medal created by Bertoldo di Giovanni in 1478 on behalf of Lorenzo de’ Medici. The depiction is what we might call “shaped truth.” What we see is the version of events that Lorenzo de’ Medici wanted to convey to the public. The depiction reflects Angelo Poliziano’s account exactly. His text was not historiography in the modern sense, but a highly complex work of propaganda. Poliziano used ancient models and stereotypes of the traitor, as Dante had created them for his Inferno. Like Bertoldo di Giovanni, he worked on the instructions of Lorenzo de’ Medici, on whom he was completely dependent financially and politically.

In his exhibition catalog “The Pazzi Conspiracy: Power, Violence, and Art in Renaissance Florence” Karsten Dahmen has meticulously reconstructed who and what exactly can be seen on the medal. This gives us an insight into how Lorenzo de’ Medici influenced the perception of history to this day.

First of all, unlike ordinary medals, the medal is not divided into front and back. Instead, we see two completely equal sides, which are in turn divided into top and bottom.

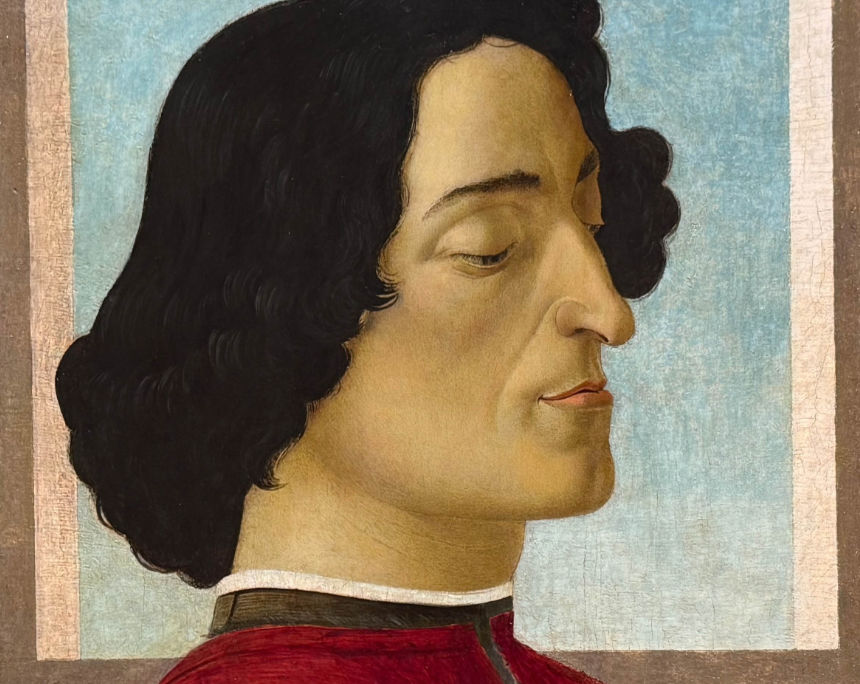

One side is dedicated to the surviving Lorenzo, the other to the murdered Giuliano de’ Medici. Both show a portrait in the upper third, labeled LAVRENTIVS MEDICES and IVLIANVS MEDICES, respectively. Below Lorenzo’s portrait is the comment SALVS PVBLICA (= public welfare), and below Giuliano’s is LVCTVS PVBLICVS (= public mourning).

The Murder of Giuliano de’ Medici

Below is a depiction of the assassination. We see the choir area, separated from the rest of the church by the choir screen. The main celebrant is deep in prayer before the altar, as are the deacons reverently assisting him and the clergy gathered in the choir stalls.

Whether the painting depicts the exact moment of transubstantiation, which some historians claim was the time of the assassination, cannot be verified. However, it is clear to every viewer that this cannot be the blessing with which every Mass ends. The Pazzi-friendly tradition says that it was the closing words of the blessing, “Ite missa est,” that signaled the assassination. That would mean that the act actually took place after Mass. What we consider to be a subtle distinction was of utmost importance to the devout Christians of Italy, so Lorenzo had his version of the timing immortalized on both sides of the medal.

The event is divided into two parts, as in a modern comic strip. The artist chose to depict the assassins naked. Not in the sense of the heroic nudity of antiquity, but like sinners in hellfire, defenselessly exposed to the torments of hell.

On the left in the middle, we see Giuliano raising his unarmed(!) hands imploringly to the sky. Bernardo Bandini approaches from one side to stab him in the side with his sword; Francesco de’ Pazzi approaches from the other side. He rams his sword into Giuliano’s chest. Giuliano collapses – and this brings us to the scene on the right – while his murderers pierce the dying man’s body with 19 knife stabs.

Lorenzo de’ Medici escapes

The events on the other side are reminiscent of Lorenzo’s successful escape. Unlike his brother, he did not appear unarmed in the church, but carefully concealed a sword. This was actually a complete breach of church rules, but the Medici family expected an attack. That is why they rarely appeared in public together. However, they could not risk doing so at the service in honor of the newly appointed cardinal. The assassins had counted on this…

They did not anticipate Lorenzo’s preparations. On the medal, he defends himself with a sword and a flowing cloak (which will soon play a role), while two assassins pursue him. Their sword blows injure him on the neck, but not seriously. In the field on the left, the horror of the observers is widely expressed, some of whom stand speechless, while others flee the church.

Meanwhile, Lorenzo, his cloak now wrapped around his arm like a shield, fights another attacker with his sword before swinging himself over the choir screen and seeking safety behind the sturdy doors of the sacristy. Karsten Dahmen wants to explain the two figures that can be seen behind the choir screen, between the deacons and the triangular lectern.

Find out more in the current exhibition at the Berlin Coin Cabinet

Have we piqued your curiosity? Then you should definitely visit the current special exhibition at the Berlin Coin Cabinet. This wonderful medal and the exhibition will be on display there until September 20, 2026.

Karsten Dahmen and Neville Rowley have designed several display cases around the object, using items from the museum’s own collection and loans from other Berlin museums to bring the exciting era of the Renaissance to life. Coins and medals illustrate the economic and political background to the assassination and its consequences. This exhibition is a good example of how huge blockbuster exhibitions are not necessary to convey historical facts.

The curators show the masterful skill with which Lorenzo staged the events and his revenge. He stylized his escape as divine justification for the Medici’s rule, which his descendants repeated until their version became (perceived) historical truth.

And that brings us to the two sides of every coin (and medal). Today, history condemns the Pazzi as murderers. Had they prevailed, we would probably know them as Florentine freedom fighters.

Because who is right is always a question of interpretation and tradition. That is why there is really only one historical truth: violence is never a solution, regardless of whether it is used for a “good” or a “bad” cause.

Text by Ursula Kampmann