Kill the profiteers!

Do you still believe that German farmers started their great war in 1524 because of the Reformation? Forget it. Farmers are far too sensible for that. They feared for their livelihoods because the feudal lords were keeping more and more of their earnings for themselves.

Money for the big guys – money for the little guys

We consider the taler to be the typical coin of the Reformation, even though very few people used it for payment at the time. This heavy coin, made of just over 27 g of fine silver, was far too precious to be used to buy daily bread. Instead, people used pennies and hellers, kreuzers, batzen or groschen, depending on where they lived. A small loaf of bread, for example, cost half a penny, a chicken 2 pennies, and a pound of beef 3 pennies, although prices varied from place to place and were constantly rising.

This was because inflation was rampant! Governments needed more and more money to build city walls, hire mercenaries, and maintain their image. Raise taxes? That was not an option. There was no value added tax or income tax. So the state took its share of the turnover by selling small coins. Anyone who wanted to trade at the market had to exchange their old money for new money for a fee.

Only the taler retained its value. But to earn one, a farmer had to sell a great many eggs, chickens, or beans. Every time he exchanged his pennies for a taler at the money changer, he paid a higher exchange fee.

The people of that time were just as smart as we are. They realized what their authorities were doing.

Revolt!

They fought back and took up arms. It began in June 1524 in Stühlingen, a tiny village in the southernmost part of the empire. A local conflict escalated into the great Peasants’ War, a mass uprising that even Emperor Charles V feared.

The Esslingen Imperial Coinage Act

It wasn’t that he was unaware of the economic problems. At the beginning of the year, the Reichstag had already debated how to get the constant deterioration of the coinage under control. In November 1524, the Esslingen Imperial Coinage Act stipulated that talers and small coins should henceforth have a fixed ratio.

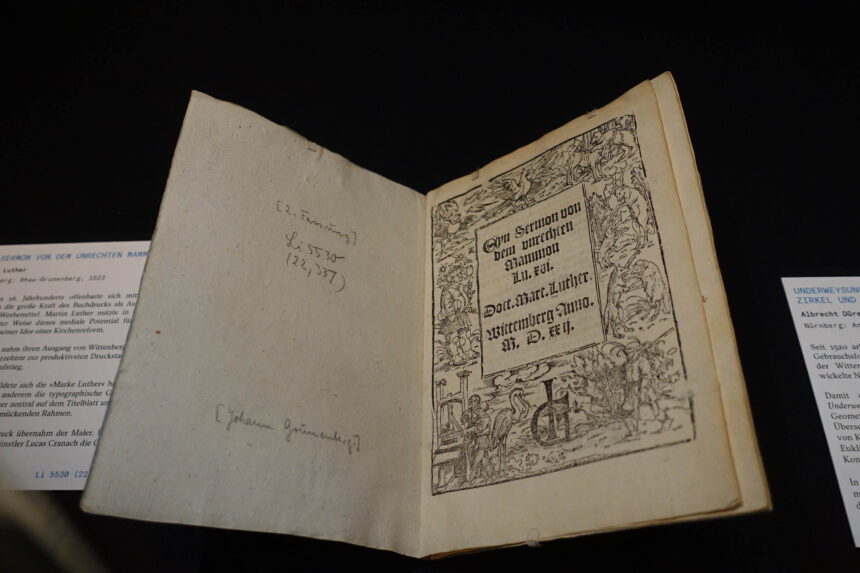

The alliance between the new religion and the peasants

Of course, this did not work. The demands of the Esslingen Imperial Order were economically unfeasible. In addition, the Peasants’ War had taken a new direction in the winter of 1524. Luther had repeatedly spoken out against usury and coin debasement. The peasants knew this too. Now the reformer Thomas Müntzer went even further. He demanded that the rulers should submit to the theologians. (He spoke, of course, of the word of God, but interpreted by Protestant theologians, and preferably by himself.) In alliance with the peasants, Müntzer attempted to create a new world without secular authority. Martin Luther sensed that this would have meant the end of his Reformation. So he first urged the peasants to make peace. When they did not obey him, he demanded that the princes “smash, strangle, and stab them, secretly and publicly, whoever can—as one kills a mad dog.”

For Luther relied on his alliance with the rulers. Together with them, the Protestant Church enforced a level of submission among its subjects that had never been seen before.

Text by Ursula Kampmann