Tracing a Legendary 238-Year Provenance and Updating the British Museum’s Record

“[…]the old world[…]its precious coins[…]its history of art. Out of these cabinets, there smiles upon us an eternal spring of the blossoms and flowers of art, of a busy life ennobled with high tastes, and of much more besides. Out of these form-endowed pieces of metal, the glory of the Sicilian cities, now obscured, still shines forth fresh before us. […] Sicily and Nova Græcia give me hopes again of a fresh existence.”

-

Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, on seeing the ancient coin collection of Prince Gabriele Lancillotto Castelli of Torremuzza, Marques of Motta d’Affermo. Palermo, Thursday, April 12, 1787. From Italienische Reise, translated into English in 1881 by the Rev. A.J.W. Morrison, MA. (von Goethe p. 51)

On a crisp spring day in 1787, the most influential writer and polymath in the history of the German language met the most influential numismatist of the 18th century. What sprung from that meeting between Johann Wolfgang von Goethe and Prince Gabriele Lancillotto Castelli of Torremuzza was a reinvigoration of Goethe’s love of the ancient world. Goethe, evidently ebullient and inspired as we can tell from his record of the meeting, brimmed with “hopes again of a fresh existence.”

What Goethe captured with his words is the reason why so many of us collect. For him, the ancient coins he saw that day in Sicily were so much more than pieces of metal. They represented the aesthetic best of civilizations that valued the pursuit of beauty, and endured as testaments to some of the finest epochs of art history. Millennia removed from their manufacture, they still transport us to times far beyond our own, mirroring our wonder in the silver-eyed gaze of Arethusa.

When we read such passionate words from one of the great minds of our collective history, we are also left to wonder: Just what exactly did Goethe see that day? What were the scenes and portraits of classical antiquity that lit up his excitement? What were the specific coins? These are questions that are too fascinating to leave solely to the imagination and to flights of fancy – they deserve academic rigor and attention. But where to start?

Sometimes, academic discoveries begin with methodical diligence, and sometimes they begin with pure luck and curiosity. While selecting catalogues for the Sixbid Classical Archive, I came across Hess Divo’s printed copy of the 1859 Sotheby and Wilkinson sale of the collection of the Lord Northwick. Among the annotations were records of exceptional sale prices of coins to the most prominent collectors of the day and institutional buyers such as the British Museum, but the full collection regrettably was not published with plates upon Northwick’s death. For the purposes of the archive, its uses were limited. While reading the catalogue, however, I learned that Northwick had a selection of his cabinet engraved under the supervision of George Henry Noehden and the British Museum in 1826. Naturally, Hess Divo happened to have a copy of Noehden’s work in its extensive library.

While reading Noehden, I came across a startling statement of provenance from the British Museum publication: “[This] coin belonged to the cabinet of Prince Torremuzza, and came, by the purchase of that collection, into the possession of Lord Northwick.” (Noehden p. 16). Instantly, I thought of Goethe – was this obscure publication a key to finding coins from that famous meeting? The hunt began.

Further context was found in the preface: “[…]Lord Northwick, during his residence in Italy, between the years 1790 and 1800, became acquainted with Antonio Canova, [the renowned Italian Neoclassical sculptor][…] His Lordship’s exquisite collection furnished abundant examples; and it was Canova’s opinion that some of these smaller works of sculpture possessed a merit, not to be surpassed by the greatest performances. The idea suggested itself of making drawings of some of the finest coins[…]” (Noehden p. 10). Unfortunately, Noehden, who was commissioned to oversee this project in collaboration with the British Museum, died in 1826 after only twenty coins were engraved and described. The engravings that were completed, however, are exceptional.

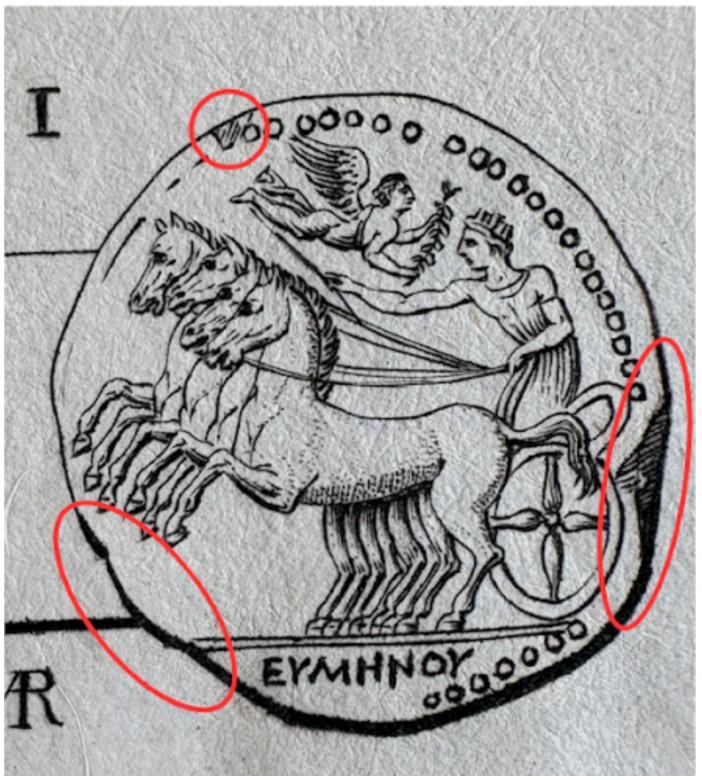

The Prince of Torremuzza died in 1794, so the claim that Lord Northwick purchased the coins from his estate while residing in Palermo at the time is a reasonable one. Sure enough, coins purported to be from Torremuzza’s collection were among those engraved in the Noehden publication, including this magnificent Sicilian tetradrachm from Katane:

This tetradrachm, signed by one of the greatest celators of classical antiquity, Euainetos, was evidently a candidate for one of the Sicilian coins that inspired Goethe to write with such effusive praise. But a troubling question remained: Where exactly did it go? It is difficult enough to find extensive provenances with the aid of photography, but tracing the unbroken provenance of a coin into the photographic era is especially challenging.

Fortunately, the Hess Divo copy of the Northwick sale contains handwritten inscriptions of the buyer names for every lot. This coin, lot 258 in the sale, was acquired by the British Museum, and so has an unbroken provenance to today. Conspicuously, the Prince of Torremuzza provenance is missing from their current collection records, despite Noehden publishing this on behalf of the Museum in 1826. This is what this gorgeous coin looks like today, with some of the deepest cabinet toning that you are likely to see on a silver coin:

Did Goethe hold this very coin in his hands? It is possible. As noted in the proceedings of the XV International Congress of Numismatics (Bateson pp. 72-74), we have record that a British Numismatic Society Fellow named Matthew Duane acquired the prince’s first Sicilian collection en bloc in 1776 (much of which is now in the Hunterian Collection), a man referenced frequently in Torremuzza’s work. Considering that this coin was in the possession of Northwick, and if we presume the provenance assertion by Northwick and Noehden to be true, it had to have been acquired by Torremuzza after the 1776 sale to Duane. The Sotheby’s cataloguer in the Northwick sale also referenced an engraving in a 1781 publication by the prince. Unfortunately, I confess, either the reference is incorrect or the engraving in question is so egregiously inaccurate and terrible that I refuse to display it.

So we can do better.

We at least have some clues to work with. We know that the British Museum purchased numerous coins from the estate auction of the purported owner of the post-1776 Torremuzza cabinet. So for the sake of relative simplicity, we can search for coins in their collection that have an 1859 acquisition date from Sotheby’s / Northwick. Because we are looking to specifically find coins that Goethe may have seen, we are primarily focused on finding a convincing engraving match in one of Torremuzza’s works published after 1776 but before April 12, 1787 (as any coins published after that date could have been acquired after the meeting unless noted otherwise by the prince). His only publication that is of particular relevance for this search, then, is his 1781 work, Siciliae Populorum Et Urbium Regum Quoque Et Tyrannorum Veteres Nummi Saracenorum Epocham Antecedentes. I consulted the copy in the special collection of the Zentralbibliothek Zürich.

Unfortunately, identifying coins based solely on the engravings published in this volume would be an exercise in madness. The engraver employed by Torremuzza, Melchior de Bella, while occasionally accurate, had fanciful tendencies for embellishment. Silvia Mani Hurter was less generous in her 2008 article Toremuzza’s SEGESTANORVM, lamenting: “It is a pity that this draughtsman did not have the slightest feeling for style…” (Hurter p. 114). Except in cases in which a coin is very distinctive from other examples of its type (which we will soon see), these engravings alone often can’t tell us much. Further complicating the situation is that not all of the coins in the Veteres Nummi were owned by the prince. Many of them were in the possession of museums, and many others

came from notable collectors such as Duane. So discerning which coins were Torremuzza’s requires us to also read the accompanying Latin text.

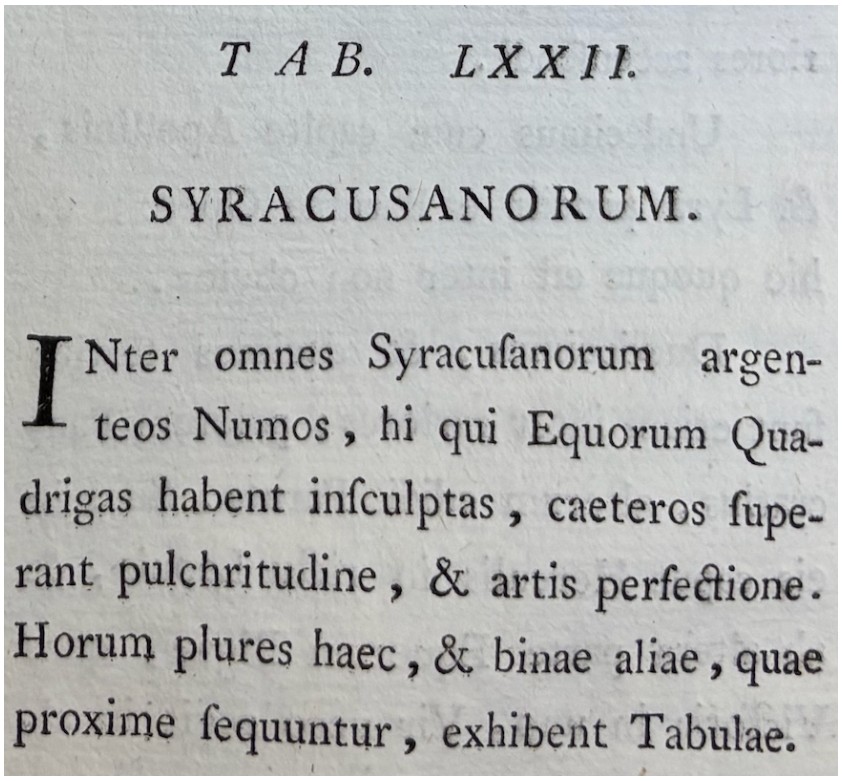

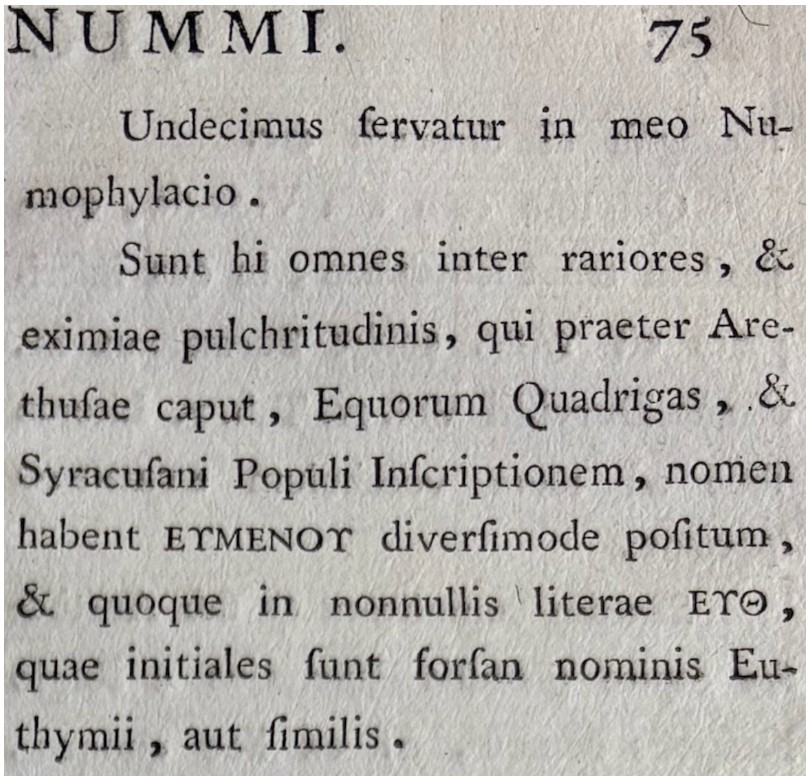

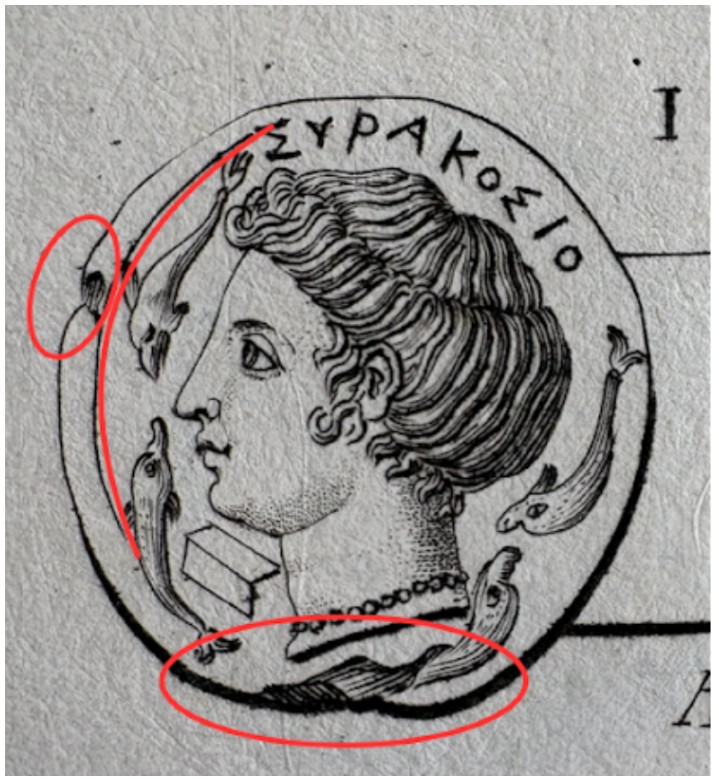

And yet, after scouring the plates and translating the Latin of this nearly 250 year-old book, I found at least one convincing match of a distinctive coin – a dramatically toned silver tetradrachm signed by two of Ancient Syracuse’s premier celators, Eukleidas and Eumenos, with Eukleidas’s portrait of Arethusa rendered in an especially exquisite style. In his accompanying text, the Prince of Torremuzza directly states his ownership of the engraved tetradrachm from Tab. LXXII, 11: “Undecimus servatur in meo Numophylacio.” (Castelli p. 75)

This engraving is still far from perfect, displaying some obvious embellishments and inaccuracies. Melchior de Bella evidently gave up on trying to read the minutely rendered Ancient Greek signature of Eukleidas on the diptych below the chin of Arethusa. He also omitted the sigma at the end of the civic legend, perhaps mistaking it at a distance for a trace of the adjacent dolphin’s tail, and he slightly reduced the size and extent of flan imperfections.

-

This coin was owned by the Prince of Torremuzza after the Duane sale, and was engraved in 1780 and published by him in 1781.

-

The fact that the British Museum acquired this coin from Lord Northwick appears to confirm that Northwick directly purchased Torremuzza’s post-1776 collection, or at least a portion of it.

-

As Lord Northwick acquired this coin from his purchase of Torremuzza’s cabinet, presumably upon the prince’s death in 1794 but not before Northwick’s arrival to Palermo in 1790, this coin was still in the possession of the prince on April 12, 1787.

-

If the rightfully proud prince indeed showed his entire reformed Sicilian and Magna Graecian cabinet to Goethe (which considering Goethe’s legendary inquisitiveness is by no means a stretch), then Goethe saw and perhaps held this remarkable coin.

-

Goethe wrote about how Torremuzza’s Sicilian coins inspired him with “hopes again of a fresh existence.” This Syracusan tetradrachm numbered among those coins.

-

This updates the British Museum’s provenance record for this coin.

—

A note to collectors: Similar examples to both coins featured in this article can appear on the private market. An example of the same type as the Katane tetradrachm sold at Gorny and Mosch this year, and another of the same type as the Syracuse tetradrachm sold at Künker the year prior. Should you wish to acquire a similar piece, or another that Goethe himself could have marveled at, contact Hess Divo and we will be happy to assist you.

-

Bateson, J. D. “Dr. Hunter and the Prince of Torremuzza’s Sicilian Coins.” Proceedings of the XV International Congress of Numismatics, International Congress of Numismatics, 2015, pp. 72–74.

-

Castelli, Gabriele Lancillotto, et al. Siciliae Populorum et Urbium Regum Quoque et Tyrannorum Veteres Nummi Saracenorum Epocham Antecedentes. Palermo, Typis Regiis, 1781.

-

Hurter, Silvia Mani. “Torremuzza’s SEGESTANORVM.” American Journal of Numismatics (1989-), vol. 20, 2008, pp. 113–17.

-

Noehden, George Henry. Specimens of Ancient Coins, of Magna Graecia and Sicily: Selected from the Cabinet of the Right Hon. the Lord Northwick. London, The British Museum, 1826.

-

S. Leigh Sotheby & John Wilkinson. Catalogue of the First Portion of the Northwick Collection of Coins and Medals, Comprising the the Greek Series. London, J. Davy & Sons, 1859.

-

von Goethe, Johann Wolfgang. Letters From Switzerland and Travels in Italy. Translated by The Rev. A.J.W. Morrison, London, George Bell & Sons, 1881.